MARJORIE LEE PIANO STUDIO

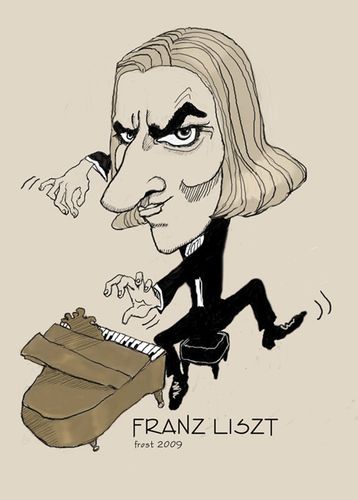

FRANZ LISZT BASH!!!

November 19, 2022

Group 1: Labunski Theme & Variations 1 & 2 from 4 Variations on Theme by Paganini

Avery Elston

Sophia Elston

Chiaoyang Qu

Evan Hou

Eva Huang

Theodore Kim

Ryan Qin

Sandy Chou

Valentina Song-Ye

Ellie Zhao

Ian Ji

Alexander Li

Group 3: Liszt Etude Op. 1 no. 4

Iris Zhou

Kelly Ji

Emma Hou

Nora Sun

Nora Ma,

Bowen Wu

Angelina Song-Ye

Dakota Man

Group 4: Liszt Grandes Études de Paganini, S. 141 - No. 4 in E Major

Ellie Nguyen

Samantha Ren

Zachary Qin

Gregory Peng

Charlie Zhao

Ellie Jiang

Ronen Wang

Group 5

Thai Nguyen

Sophia Lin

Zack Lam

Clark Hu

Hiroki Matsui

Claire Peng

Who was the first ‘modern’ pianist? Whatever else the world may debate about his life and work, one thing is generally conceded: Liszt was the first modern pianist. The technical "breakthrough" he achieved during the 1830s and '40s was without precedent in the history of the piano—all subsequent schools were branches of his tree. The first indication of this breakthrough had come in 1837-39 with the appearance of the Douze Grandes Études; these works (along with the early Paganini studies) represented a treasure of keyboard resources not found in any earlier work. Their first version dates back to 1826—Liszt would now take these juvenile exercises and transform them into works of towering difficulty. After they were published by Haslinger of Vienna, a review copy found its way into the hands of Schumann who astutely observed their connections with the juvenile pieces, overlaid though they are with monstrous technical complexities, and described them as "studies in storm and dread for, at the most, ten or twelve players in the world." It was partly as a result of Liszt playing his Grandes Etudes in public, under widely varying circumstances, that he revised them yet again as "Études d'exécution transcendante", smoothing out their more intractable difficulties; however, modern scholarship has done a disservice to Liszt by suppressing the two earlier versions, arguing that they do not represent Liszt's final thoughts. For Liszt, a composition was rarely finished, all his life he went on reshaping, reworking, adding, subtracting (sometimes a composition exists in 4 or 5 different versions simultaneously!). To say that it progresses towards a "final" form is to misunderstand Liszt's art; entire works are "metamorphosed" across a span of 25 years or more, accumulating and shedding detail along the way. It may of course not be essential to learn the early models before one plays the Transcendentals well, but it will certainly colour the player's attitude towards them, in a positive sense, and will bring him more closely into line with Liszt's own attitude towards them, if he hears the Transcendentals over that same musical background against which Liszt himself composed them. The modern pianist may disparage Liszt's studies (it has certainly become trendy in the YouTube comment section to do so) but he should be able to play them, otherwise he admits to having a less than total command of the keyboard (what harsh words have been uttered against Liszt's virtuosity, usually by those who could not match it! How strongly has it been attacked in the name of "Art"! Yet virtuosity is an indispensable tool of musical interpretation; one recalls Saint-Saëns's telling aphorism: "In Art, a difficulty overcome is a thing of beauty.").

The Tenth Study, usually accounted to be the finest of the 1851 set, is even more imposing in the 1837 version, although Liszt’s later solution for the layout of the opening material produces a more restless effect by eliminating the demand for playing melody notes with the left hand in amongst double sixths in the right. In a very solid sonata structure, the 1837 text does not break the flow towards the end of the development, but does ask for some very awkward playing of enormous stretches. (Liszt’s hand almost certainly contracted as he grew older: Amy Fay reliably reports that the old Liszt could just take the black-note tenth chords at the end of the slow movement in Beethoven’s ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata). The 1837 version also has a much longer coda, which abruptly changes meter and becomes ferocious, and is (at times) right on the edge of the possible.

Andrei Cristian Anghel